I've never been one for rallies, regardless of how worthy their causes are. It's just that it seems so extremely rare that they actually result in something that wasn't going to happen anyway, via other means; and also, I cringe about generic complaint that isn't tied to clear and specific policy solutions.

As such, I find it annoying to watch media and social media coverage of who was rude to who (the PM, or a female activist who, rather suspiciously, was happy to go on a clear right wing media outlet - Ben Fordham radio show, apparently - to complain about what happened.)

Anyway, I am left rather unclear as to what policies apart from "less bail - look them up longer" are being discussed - and what activists think a federal government can do when virtually all of these offences are going to be dealt with in the State systems.

Bernard Keane had a column in Crikey which suggested that the punishment (or potential for it) is the answer. Unfortunately, it is now behind the paywall, but he drew a comparison with what happened with the introduction of random breath testing - the risk of being caught and the severity and disruption of the punishment had a clear and immediate effect on offending and road deaths.

However, he was also brave enough to point that increased use of imprisonment for domestic violence offenders is going to mean a worse outcome for the rate of aboriginal incarceration, given that it is well known that the rates of domestic violence are way higher amongst that group.

Sarah Williams, as it happens, is apparently indigenous.

I think it is safe to assume that there is a fair cross over between the types of people who would turn up at a "stop domestic violence" rally and those who would also attend any type of "treat the indigenous better" rally. Are they going to be big enough to admit that increased jail is going to increase the rate of indigenous incarceration that they are, presumably, normally against?

The public debate about crime and social issues is so often, I reckon, ill informed (or uninformed) about the big picture. It used to be that criminologists (well - I can only remember one, to be honest - Paul Wilson) would turn up on TV to talk about crime and punishment and what works. (Amazingly, though, he himself ended up in prison for a historic child sex offence!) But, from what I can recall, he did used to bring a fairly calm and useful contribution to crime and justice issues of the day.

We seem to be lacking that now. I mean, research is done, but it doesn't get well discussed. Look at this report by the Productivity Commission, of all places, about how incarceration rates have increased in Australia over recent decades:

The past 40 years has seen a steady rise in the level of imprisonment in Australia and the imprisonment rate is at the highest level in a century. The number of prisoners per 100,000 adults has more than doubled since the mid-1980s and increased by 40 per cent from 2000 to 2018.

These numbers wrongly suggest some sort of Australian ‘crime wave’. In fact, the data shows the opposite trend. The offender rate has been falling. The number of offenders proceeded against by police per 100,000 population fell by 18 per cent between 2008‑09 and 2019‑20, while the imprisonment rate rose by 25 per cent over the same period.

Australia’s rate of growth in imprisonment is out of line with other developed countries. UN data show that Australia’s growth rate in imprisonment was the third highest among OECD countries between 2003 and 2018 – exceeded only by Turkey and Colombia.

Put simply, we have fewer criminal offenders but more people in prison.

How do we explain this?

The answer matters. Prisons are a key part of the criminal justice system and help keep the community safe. But:

- Prisons are expensive, costing Australian taxpayers $5.2 billion in 2019‑20 - more than $330 per prisoner per day. If Australia’s imprisonment rate had remained steady, rather than rising over the past twenty years, the accumulated saving in prison costs would be about $13.5 billion today.

- While there were 40,000 Australians in prison on 30 June 2020, many more flow through the prison system over the course of a year. Around 60 per cent of those in prison have been there before and around one third of convicted prisoners receive a prison sentence of less than six months. So, a substantial sub-group of the Australian prison population appears to be stuck in a prison-crime-prison revolving door.

Anyway, I don't have time to dig deeper, but how many people in Australia would even know that incarceration rates have increased in this period? (I didn't realise it was so high, myself.)

So, this post is just a call for decent criminologists (ones without criminal acts in their own past, preferably) to get on the front foot about research and what works - or seems to work - in other countries. And do it objectively, without an ideological axe to grind (such as complaining about historical mistreatment of indigenous.)

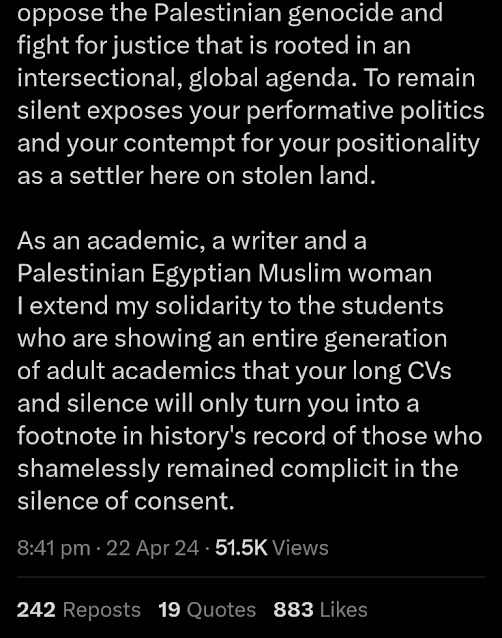

%20Randa%20Abdel-Fattah%20(@RandaAFattah)%20_%20X.png)

%20Prof%20Sandy%20O'Sullivan%20(Wiradjuri)%20%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%20(@sandyosullivan)%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20New%20York%20Times%20Pitchbot%20(@DougJBalloon)%20_%20X.png)

%20George%20Conway%20on%20X%20%E2%80%9CThings%20have%20changed%20a%20lot%20since%20I%20talked%20to%20folks%20outside%20of%20Trump%E2%80%99s%202016%20rally%20in%20Chester%20County%20when%20they%20were%20intrigued%20by%20Trump%E2%80%99s%20not-a-politician%20blust%5B...%5D.png)

%20George%20Conway%20(@gtconway3d)%20_%20X.png)

%20Tom%20Joseph%20on%20X%20Trump%E2%80%99s%20dementia%20deterioration%20is%20very%20evident%20here.%20This%20is%20what%20it%20sounds%20like-%20mindless%20word%20drool.%20He%E2%80%99s%20had%20it%20for%20a%20while%20and%20it%20continuously%20worsens%20so%20he%5B...%5D.png)

%20Tom%20Joseph%20on%20X%20Trump%E2%80%99s%20dementia%20deterioration%20is%20very%20evident%20here.%20This%20is%20what%20it%20sounds%20like-%20mindless%20word%20drool.%20He%E2%80%99s%20had%20it%20for%20a%20while%20and%20it%20continuously%20worsens%20so%20he%5B...%5D.png)

%20Tom%20Joseph%20on%20X%20Trump%E2%80%99s%20dementia%20deterioration%20is%20very%20evident%20here.%20This%20is%20what%20it%20sounds%20like-%20mindless%20word%20drool.%20He%E2%80%99s%20had%20it%20for%20a%20while%20and%20it%20continuously%20worsens%20so%20he%5B...%5D.png)

%20Nancy%20T.%20@OldEnuf2KnowBtr%20on%20P%20st%20on%20X%20@TomJChicago%20I'm%20wondering%20if%20Vegas'%20bookies%20are%20starting%20to%20calculate%20the%20odds%20of%20him%20making%20it%20to%20November.%20_%20X.png)

.jpg)

%20Prof%20Sandy%20O'Sullivan%20(Wiradjuri)%20%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%20(@sandyosullivan)%20_%20X.png)

%20Will%20Stancil%20(@whstancil)%20_%20X.png)

%20Will%20Stancil%20(@whstancil)%20_%20X.png)