I went and saw the well reviewed movie Everything Everywhere All at Once on the weekend, and as it happens, this is the second Hollywood (or TV) prompt to talk yet again about Buddhism, as I recently (finally) finished watching the last season of The Good Place, and the final few episodes incorporated Buddhist ideas too.

First, the movie as an experience: I enjoyed it and thought it well worth seeing, and it's definitely the type of movie that is great to see with someone who wants to talk about its merits and problems afterwards. It isn't perfect, and I reckon has been somewhat too highly praised for what it is - a relatively low budget science fictiony jumble of mixed philosophic messages and emotional themes that drown a bit in the somewhat sophomoric urge to rely on extreme silliness for laughs. (I share broadly the sentiment in this Washington Post review.) I mean, I did laugh, but if I were a movie producer, I would have encouraged dropping some of the silliest bits, and the movie would be better shortened by about 10 or 15 minutes anyway. On the upside, it is surprisingly well acted by all, and hearing "Short Round" as an excitable adult was particularly pleasing. I did find it touching, too. Yet I wish it dealt with the issues of the meaning of life in a somewhat clearer fashion. Still, it is great to see original content of this type in the cinema again.

NOW FOR THE SPOILER WARNING

First, I want to talk about the nature of the multiverse in this movie. Maybe I am mistaken, it seems early in the movie that the "splitting" is reliant mainly on individual choices; but then again, in one sequence it's explained that most universes end up without the conditions suitable for life, which would indicate that it is the "Many Worlds" of quantum mechanics. Does the Many Worlds theory allow for individual life choices to be a form of "measurement" that cause a split? I'm not entirely sure. [And, to get technical, a video I watched this morning explains how Many Worlds works by removing the measurement problem. But I still think you have to have something that is like a measurement for a split to happen.] I guess it doesn't matter much, except that the idea of a (near?) infinite number of lifeless multiverses tends to point one more strongly to the "nothing matters" nihilism that is one of the suggestions of the movie.

The clearest Buddhist vibe I got from it was the all knowing version of the daughter wanting to achieve annihilation by entering the black hole-ish bagel of doom. It strongly suggested the idea of nirvana and a full dissolution of the idea of the self as an end to suffering. There is a short thread on Reddit in which a few people comment on the Buddhist aspects, although none specifically mention nirvana.

The movie does raise the ambiguity of Buddhist thought which seems on one level to suggest "nothing matters", but on the other, that it is important to respond to the universe's meaninglessness with kindness (or compassion, being the favoured Buddhist term) to others.

If I Google "Buddhism and nihilism" there is lots of discussion of the topic - with Buddhists arguing that the "no self" and their view of the world is not really nihilistic at all. Some also raise the connection with existentialism - it's pretty obvious.

There is always the argument, I guess, that if you can recognise that compassion has purpose and "meaning", it's not really a meaningless universe already. CS Lewis used to argue this, and while I don't think it's a perfect argument, it still has an intuitive appeal.

There are two ways of thinking about how meaning in the universe could be derived: one from the top down (the Gods set the rules, or may be subject to the rules themselves); the other is from the bottom up (existentialism, or the Tiplerian idea that sociobiology and economic games theory means that altruism and love are the natural order of the universe.) I still like Tipler's idea that it's really all a circle (annoyingly, that bland earworm song from Lost Horizon frequently pops into head when I think about this) - so that the future superintelligence that becomes God has to incorporate love and altruism, and at the end of time also kicks off the whole Big Bang. Unfortunately, since his prediction of the mass of the Higgs boson did not work out, I don't know whether he is depressed now or has come up with a work around.

There's also the Tolstoy (and I suppose, Kierkegaard) approach of just saying this is beyond the reach of rationality, and you take it on a leap of faith. From Toltstoy, working out a solution to his depression caused by peaking relatively young, and thinking too much:

Philosophic knowledge denies nothing, but only replies that the question cannot be solved by it — that for it the solution remains indefinite.

Having understood this, I understood that it was not possible to seek in rational knowledge for a reply to my question, and that the reply given by rational knowledge is a mere indication that a reply can only be obtained by a different statement of the question and only when the relation of the finite to the infinite is included in the question. And I understood that, however irrational and distorted might be the replies given by faith, they have this advantage, that they introduce into every answer a relation between the finite and the infinite, without which there can be no solution.

So that besides rational knowledge, which had seemed to me the only knowledge, I was inevitably brought to acknowledge that all live humanity has another irrational knowledge — faith which makes it possible to live. Faith still remained to me as irrational as it was before, but I could not but admit that it alone gives mankind a reply to the questions of life, and that consequently it makes life possible.

Perhaps someone in the Reddit thread summarises the movie well enough:

The overarching theme of the movie is "nothing matters". I believe that a central question in Buddhism is "if nothing matters, then what is the point of life?"

When the daughter sees the infinite possibilities of the multiverse, she embraces chaos takes a path of destruction. In particular, she shuns happy moments since she sees they always come to an end.The father sees this chaos and dedicates his live(s) to fighting it.

The father says something along the lines of "I choose to fight with love", and even pleads with everyone to stop fighting in the finale.

When the mother discovers the multiverse, she sees that there's no point of chasing "what ifs" and regrets. Instead, she learns to live in whatever universe she happens to be in and embrace the few moments of meaning and joy, but also the sadness and suffering that comes along with it.

I believe that these three behaviors reflect the unenlightened and enlightened perspectives -- embracing chaos or chasing the good moments of life are both fruitless efforts. Ultimately, the path to living life without suffering requires being unattached to the highs and lows while still accepting and living in them as they come.

It still gives the impression of Buddhism as a sort of emotionally deadening religion/philosophy, though: as if the ideal is not to feel too strongly about anything. And it still raises the question of whether something has to matter in order to be concerned that "nothing matters"? Also, the Dalai Lama seems pretty happy (and his branch of Buddhism is not even my favourite.) That suggests that embracing happiness is fine.

This is something I still need to read more about....

Oh, and I suppose I should discuss briefly the ending of The Good Place, too. The afterlife underwent a re-organisation that allowed for "re-testing" - essentially it was a universal salvation scheme combined with reincarnation to learn lessons to become a better person who really does deserve "the Good Place". But the eternal heaven started to bore the saved, so "meaning" was reincorporated by allowing voluntary annihilation. And three of the four main characters did, in the final episode, decide to take that option. Not because of unhappiness, as in Everything Everywhere, but because a sense of satisfaction that everything to be done and achieved had been done. We see what happens when the last one (Eleanor) walks though the gate, and her soul dissipates into sparks of light that are seen having a positive influence on someone still on earth - sort of a diffuse bit of karma sprinkles to influence the world. More than a tad Buddhist, I'm sure you'll agree. (And the show mentions Buddhism specifically, too.)

The problem I have always had with such musings is that it's pressing rationality too far: none of us can imagine infinity as an experiential thing. It's a very dubious exercise to talk about Heaven as an infinite extension of what a good life on Earth is like, and thereby to assume that boredom with experiencing things in a temporal realm would be reflected in "life" that is outside of time.

I drawn more to the idea that individual souls can be absorbed into the Godhead:

The third view is that of the Vishishtadvaita Vedanta school. Here, liberation occurs when the soul enters into the oneness of God, rather as a drop of water merges into the ocean, while paradoxically maintaining its individual identity.

...with perhaps the possibility that the individual re-appears as needed. But this is really something that we can't get properly imagine, and it is a bit silly to build stories on it that are too detailed.

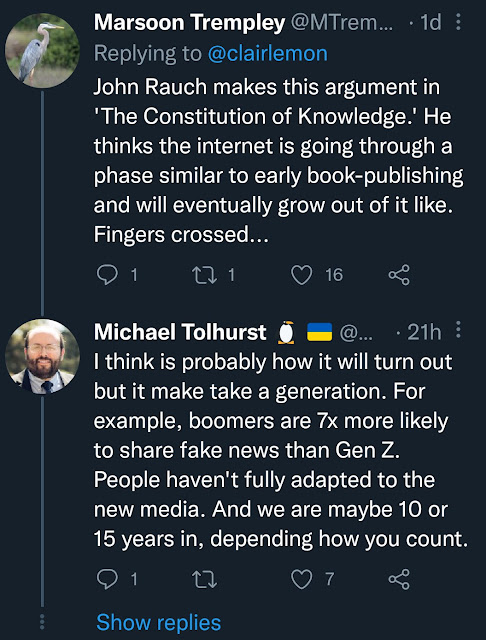

%20_%20Twitter.png)

%20_%20Twitter.png)

%20_%20Twitter.png)