Wikipedia gives a good background to the parsnip, and there are many things about this vegetable which make it rather intriguing:

1.

Cold ground improves it. Every article I have read about them refers to their sweetness, but this apparently is mainly brought on by their going through frosts before being pulled out of the ground. This may well explain why I have never considered them particularly sweet - I assume there are few grown in Australia that are held in the ground until a frost has sweetened them up. I like their flavour in any case: they have a spicier, earthier vibe compared to the fairly bland carrot (which, in Australia, I would generally consider sweeter than any parsnip I've eaten.)

This ability to winter over in the ground appears to have been a positive for their cultivation. See this from a

column in the Washington Post:

Nevertheless, nothing else does what the parsnip does: rest in the

ground all winter with no need for root cellar storage. After a few fall

frosts it develops a sweetness that no carrot has ever bested, and it

sustains that all the way into mid-spring. You can dig it any time the

ground is not frozen, but it is most treasured as the earliest fresh

harvest of the year.

2.

Food of the Emperor - we think. Emperor Tiberius, according to Pliny, took annual tribute from a part of Germany in parsnips. The only confusion appears to be whether Pliny really meant parsnips, as the carrot of the day could be pretty pale too, and there seems to still be much uncertainly about which of these vegetables any writer of that era was referring to.

There was a

detailed article on the philology of the parsnip written in 1958 which you can see in preview. It appears certain that Pliny was at least sometimes referring to parsnips specifically, but whether the author throws doubt on the Tiberius story remains unknown to me. Maybe some reader will pay the $4 for the full article and let me know.

In any event, this short explanation (from this book) of the expansion of the parsnip from ancient Roman times into the rest of Europe seems good:

3.

They are unduly expensive everywhere. Parsnips cost about $10 a kilo in Brisbane at the moment, but if you Google the topic "Why are parsnips so expensive", you'll find that their high cost has been mentioned on the internet in many countries, including England, France and America. As far as I can make out, they are a finicky vegetable to grow, with low and slow germination rates from seed, and perhaps slow growing generally. I also guess that if people know them for their sweetness, they may not bother growing them if they can't be sure they will get a frost before harvest.

It's no wonder carrots are the ubiquitous root vegetable - they are frequently so incredibly cheap in the supermarket, I am often surprised that farmers make any profit from them. I know from childhood that they are dead easy to grow at home too.

4.

Parsnips lost out to the potato. The parsnip made a successful journey across to North America, but you can Google up a chapter in a book Disappearing Foods that is called

Parsnips - now you see them, now you don't, which talks about how the vegetable slipped out of popular use from perhaps the 18th century particularly in Italy and the Netherlands. Much of the blame apparently goes to the potato, being a more reliable and easily grown crop. Apart from this, the book does make this observation about the parsnip in Dutch art:

5.

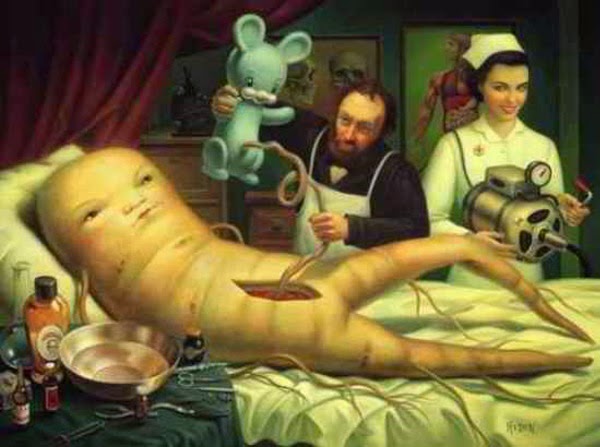

In art, when is a parsnip just a parsnip? In my previous post, I have examples of parsnips in various European paintings (although, to be honest, I haven't even looked up yet where the last two oddball paintings come from.)

But one of the more enjoyable posts about parsnips I have read

was this one, which speculates whether parsnips were (at least sometimes) deliberately put in paintings to represent sex or lust. As the writer notes, the carrot and parsnips both had developed a reputation as an aphrodisiac, one suspects for no other reason than their vaguely phallic shape:

In 1563 Culpeper states: "The garden Parsnip nourishes much, and is good

and wholesome nournishment,but a little windy, whereby it is thought to

procure bodily lust" which is pretty close to similar quotes I found on

the net. Of course there are many earlier references, such as in the

widely known "Tacuinum Sanitatis" of the 14th century where it

attributes the stimulation of sexual intercourse to the Pastinace, a

word sometimes used to describe both carrot and parsnip. An other

reference I found from the materia medica (the Taylor-Schechter Genizah

collection) dating to 11th to 14th century Cairo, depicted the parsnip

as an aphrodisiac. What is amusing, as pointed out in much of the above

references, is that it was also a wind producing food (it was said to

make you fart), this apparently was connected to the excitement (blood

flow) of certain areas.

Of course, there is more here at play than just medicinal qualities, it

also had a phallic property which pops up in Florio's Italian/English

dictionary, 1598, (cited in the OED) as the "pastinaca muranese", "a

dildoe of glasse" ... or at least this is what I was able to gather from

various sources. This is also brought to light in "Picturing women in

late Medieval and Renaissance art" (Grössinger) where she describes

parsnips and cabbages representative of male and female genitalia, and

given much of what I have read today, am inclined to agree.

The post gives a couple of examples of paintings where the parsnip on the table does seem to fit in with the general lusty context.

She also wonders why they would turn up on the table at the Last Supper, but I guess I've solved that one already in my research - presumably, they are taken to be a symbol of the nails of the cross in that case. (Either that or else Dan Brown will have some explanation involving sex.)

6.

Eat, but don't touch. One of the stranger things about the parsnip as a plant is that its sap, on skin contact, can sometimes cause a serious "burn" reaction in sunlight.

Have a look at this woman from England who got bad blisters from her garden parsnips.

Articles from North America talk about the same problem with respect to wild parsnips. The way the

sap hurts sounds complicated:

Wild

parsnip is of concern because humans develop a severe skin irritation

from contact with sap from the plant. Wild Parsnip plants have

chemicals called psoralens (more precisely, furocoumarins) that cause

phyto-photodermatitis: an interaction between plants (phyto) and light

(photo) that induce skin (derm) inflammation (itis). Once the

furocoumarins are absorbed by the skin, they are energized by UV light

on both sunny and cloudy days. They then bind to DNA and cell

membranes, destroying cells and skin.

Wild Parsnip burns usually occur in streaks

and elongated spots, reflecting where a damaged leaf or stem moved

across the skin before exposure to sunlight. If the sap gets into the

eyes, it may cause temporary or permanent blindness.

No wonder they don't seem to be all that popular in the home garden, although Wikipedia does say that this reaction does not happen to all that many people who grow them.

7.

That is all.

Update: Actually, there was another parsnip story I read some weeks ago about a farmer (English, I think) who made a killing on the sales of parsnips from his field one winter, as they were one of the few crops still available due to their ability to "over winter". I can't find the source for that now, but will keep looking. Any story of a person who got rich from parsnips seems noteworthy.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Individuals with low marginal productivity impose costs on the economy through various other correlations with drug abuse and crime and so on. But it isn’t clear that inequality is the cause of those problems.