It's one hundred years since one of the most successful public health campaigns, ever, started:

In the early 20th century, iodine deficiency was ravaging much of the northern United States. The region was widely known as the “goiter belt,” for the goiters — heavily swollen thyroid glands — that bulged from many residents’ necks.

The issue was more than cosmetic: Iodine deficiency during pregnancy and lactation often led to children with severely diminished IQ and other permanent neurological impairments.

And Michigan was at the epicenter of the crisis.

The soil there didn’t have much iodine. Nor did the freshwater Great Lakes. And so the inhabitants didn’t have much iodine, either.

The prevalence of iodine deficiency in the state became strikingly apparent after the outbreak of World War I. Simon Levin, the medical examiner for the draft board in Michigan’s Houghton County, observed that more than 30 percent of registrants had a demonstrably enlarged thyroid, which could disqualify them from military service. In fact, it was the leading cause of medical disqualification in northern Michigan.....These developments came to the attention of David M. Cowie, the first professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan. Having studied in Germany, he was familiar with the Swiss practice of adding iodine to table salt.

At a 1922 symposium held by the Michigan State Medical Society, Cowie recommended the iodization of salt, a near-ubiquitous food product that would quickly reach a large percentage of the population.....

So the Michigan State Medical Society launched an initiative to educate locals on the need for iodine. Cowie, along with colleagues from the University of Michigan and state health department workers, began delivering iodine lectures across the state. Many thousands of receptive listeners came, at a time when the American public was beginning to show an interest in vitamins, minerals and other aspects of nutrition.

Cowie also presented the case for iodization to the Michigan Salt Producers Association. The salt producers, seeing the potential for profits from the new product — and perhaps wanting to do a public service — were easy converts. They agreed to iodize salt for animal consumption as well, as many Michigan farm animals were contending with their own goiters.....

Customers still had a choice to buy iodized or noniodized salt, but increasingly they were going for the iodine. Within a decade, iodized salt accounted for 90 to 95 percent of Michigan’s salt sales. And the results were undeniable: A 1935 survey found that incidence of enlarged thyroids had decreased in the state by as much as 90 percent.

%20Home%20_%20X.png)

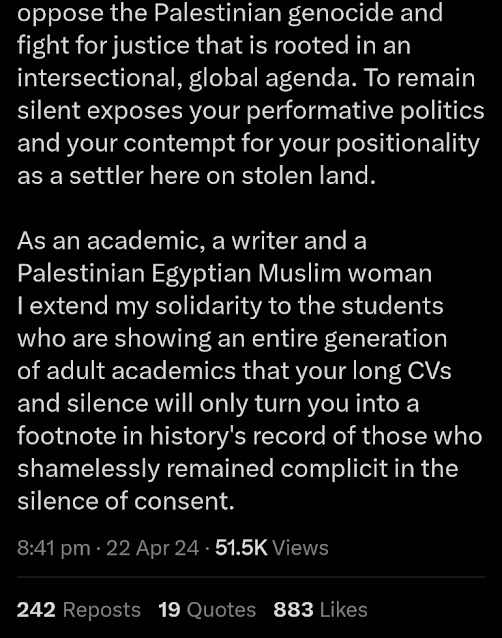

%20Randa%20Abdel-Fattah%20(@RandaAFattah)%20_%20X.png)

%20Prof%20Sandy%20O'Sullivan%20(Wiradjuri)%20%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%F0%9F%87%B5%F0%9F%87%B8%20(@sandyosullivan)%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20Dr.%20Laura%20Robinson%20on%20X%20Naomi%20Wolf%20has%20evolved%20into%20her%20final%20form%20a%20seminarian%20with%20six%20weeks%20of%20Greek%20who%20thinks%20the%20entire%20New%20Testament%20has%20been%20translated%20wrong.%20_%20X.png)

%20New%20York%20Times%20Pitchbot%20(@DougJBalloon)%20_%20X.png)